Often we hear from inventors who have spent thousands of dollars to file a patent. They’ve been through the process, completed it, and are excited about their new patent – until they find out it’s not what they thought. On the surface, that sounds quite surprising. How could you get through such an involved process and not get what you wanted?

First, a Design Patent is a much cheaper and quicker option than a Utility patent. However, suppose you have a new invention. In that case, a utility patent can be a better choice as it covers more aspects of an invention. Both patents are essential, but they cater to different consumer needs. Know the difference to make an informed decision about your invention. This article provides an overview of the difference between a design patent and a utility patent. The report details both the utility and design patents, look at their features, and if you can apply for both.

Design patents are a type of industrial design right. A design patent is a form of legal protection granted to the ornamental design of a functional item. Decorative designs of jewelry, furniture, beverage containers, and computer icons are examples of protected objects by design patents.

Inventors often overlook the option of filing a design patent application when seeking to protect their invention. To the uninitiated, a utility patent may seem like the obvious choice. After all, a utility patent protects the functionality of a new creation and not simply its appearance. But filing for a design patent can make sense in certain situations. The key to making this determination is to understand just what a design patent covers.

A design patent protects the way an article looks. Design patents are best for protecting ornamental and cosmetic features that add little functionality. If a product has improved or distinctive functional features, a utility patent could be considered instead of a design patent. Obtaining design patent protection may have advantages over utility patent protection when

(1) the cost of obtaining a design patent is substantially lower than obtaining a utility patent, and

(2) the article is one commonly purchased by customers who make their purchasing decisions based on appearance. A few examples of articles described in design patents are artificial teeth, the exterior surface of an automobile, the shape and design of furniture.

One can argue that the design patent received lesser recognition than it deserved for many years. While a utility patent focused on the actual function of the invention, to that end, a design patent received comparatively little attention. However, this situation has changed with the proliferation of attractive designs in our everyday lives. Today, the average consumer is much more aware of product designs and often will choose one product over another due to aesthetics.

Recent patent cases have dispelled a couple of myths about utility patents. For instance, you may have been operating under the impression that prior art—existing inventions or technology in the public domain—is the deciding factor in whether your idea will be patented. But that’s not exactly the case.

Ultimately, why might a utility patent be better than a design patent? A utility patent covers the functionality of an invention rather than ornamental design. Utility patents have an advantage over design patents. They can protect the way a product is used and protect parts of an apparatus that are not visible and do not fulfill a function. If something has a process, it can be covered by a utility patent; if it does not have a process, but has ornamental features, it can be protected by a design patent.

A utility patent protects how something works and what it does. Central heating is a process for keeping people warm. A bicycle is a human-powered land vehicle with two wheels. The pop-up toaster is an electrical device to toast sliced bread automatically. A utility patent would protect the process or way an invention works.

For example, the steps in a process or method or how an article is made or used. Such things as machines manufactures (things made by humans), chemical compositions, processes (ways of doing or making things), and new uses for known products are all presumed to be useful and, therefore may be patented if they are novel (new), nonobvious, fully disclosed and claim

To get a utility patent, you need to be able to make the case that the object is nonobvious. You’ll need to explain what makes it nonobvious and ideally provide some expert opinions that agree. A design patent is a lot easier. It’s just a matter of whether your design is different enough from what already exists, and I don’t think anyone will disagree.

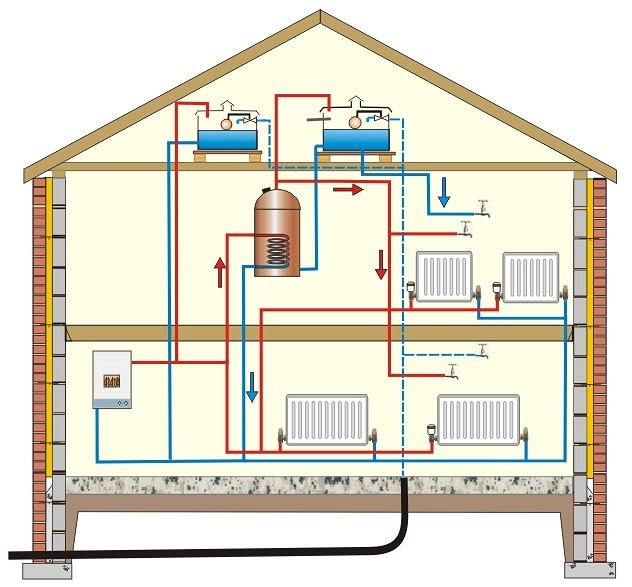

In the images to the left, you will see a two furnaces. You can easily see the design differences.

The application for a utility patent must be filed within one year of its invention’s first public use or sale to receive a patent. A design patent will expire 15 years from the date on which the USPTO first received its design. However, a utility patent can expire 20 years from its filing date if three maintenance fees are not paid on time.

Because design applications are often viewed as more specialized and technical, they may have a higher likelihood of initial rejection.

Design and utility patents may be obtained on an article if the invention resides both in its utility and ornamental appearance. A utility patent would protect the way an article is used and works. A design patent would protect the way an article looks. For example, both types of patents may be used to protect a new design for an automobile body. A design patent would protect the ornamental appearance of the body. In contrast, a utility patent would protect its functional aspects of it, such as its fuel efficiency.

Drafting a patent application is complicated. A good one can be more than a hundred pages long and involve some of the most high-level legal languages.

Patents are misunderstood. Too many people think a patent gives you the right to practice your invention. It does not. You get the right to stop others from practicing it, but only if you protect the invention yourself or license it. Suppose you invent a better mousetrap but don’t manufacture mousetraps. In that case, you’re better off licensing than suing someone using your idea. So, patents are just a defensive measure for a startup with no products.

If you run a startup, patent law is a great enemy because it lets large companies block you from making new products. It’s easy to misinterpret patents: they’re not just a description of what someone invented. They’re an instruction manual for how to sue someone later.

Getting a patent is not as simple as telling an attorney your invention and having them put it into legal language. You have to ensure that you have a patentable idea. You should check patent databases to see if there are patents issued for similar ideas, and you need to figure out the best way to describe your invention would be.

When you have a new idea that’s never been done before, you may want to consider patenting your work so that no one else can copy it. Hiring an attorney can help you decide if getting a patent is right for you and what type of patent you need to protect your project.

The Intellectual Property Attorney you hire to represent you and your business is one of the most important decisions you will ever make.

These are the values that guide this firm:

Having a lawyer is often the difference between success and failure. A good intellectual property lawyer is priceless. Without one, you’re basically out in the cold on your own. I have seen so much go wrong for clients’ businesses and even personal finances apart from the company.

– Jerry K Joseph Esq. Founding Attorney

© 2023 Law Office Of Jerry Joseph. All Rights Reserved